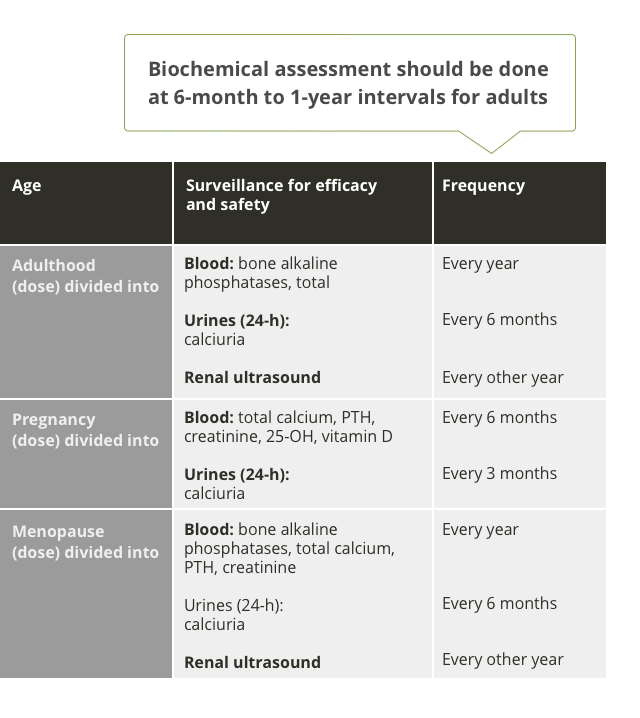

Adult assessment

Clinical assessment

To monitor ongoing, active disease, clinical assessment of weight, mobility, and pain should be conducted every year.1

Radiographic, renal, and biochemical monitoring can be used.

Radiographic

Radiographic assessment can help confirm insufficiency fractures and enthesopathies.2

Renal

Renal ultrasound should be conducted every other year.1

Biochemistry

Blood assessment of ALP, total calcium, PTH, and creatinine should be evaluated every year. Urine assessment of calciuria should be measured every 6 months.1

- Biochemical assessment

Physical function & mobility

Use tools like the 6-minute walk test to regularly assess changes in mobility and physical function.

Regular assessment

Scheduled skeletal assessment of XLH patients is indicated. The frequency of review may vary depending on symptoms and surveillance of therapy.2

Bones

Lower-limb deformity

Height reduction, severity of leg deformity, and number of surgical corrections of leg deformities are indicators of skeletal disease severity.5

Osteoarticular symptoms

Pain, reduced physical function, and poor quality of life should trigger assessment of the origin of osteoarticular symptoms via skeletal survey and evaluation of biochemical parameters for evidence of osteomalacia.1

Fractures (including insufficiency fractures and Looser zones)6

The most common areas of insufficiency fractures are the femurs, feet, and tibiae/fibulae, followed by the hips, hands, and wrists.

Indications of insufficiency fractures might include:

Insufficiency/Looser zones (Milkman zones)

- Bone pain and focal tenderness

- Worsening deformity

Nonunion

- Pseudoarthritis

Bone pain6

In a survey of 165 adults with XLH, 123 responded to questions about bone pain. Most of these adults experienced some type of bone pain.

Surgical Interventions

Persistent lower-limb bowing and/or torsion resulting in misalignment of the lower extremity may require surgery. Patients may undergo surgical treatment to straighten the lower limbs (ie, osteotomy), or they may require hip or knee arthroplasty due to degenerative joint disease and enthesopathy.2

The aim of current treatment is to improve the symptoms, not to normalize serum phosphate levels.1

Joints and ligaments

Enthesopathies are predominantly observed in those aged 40+.5

Enthesopathies are specialized attachments of tendon/ligament to bone resulting from inappropriate mineralization.8

Dental

The dominant dental feature in XLH is the occurrence of spontaneous infection of the dental pulp tissue, resulting in tooth abscesses. In contrast with common endodontic infection, these abscesses develop in teeth without any signs of trauma or decay, affecting both the deciduous and permanent dentition.1

Adult patients with dental manifestations should be referred to a dental specialist with experience in XLH for a full clinical and radiographic examination.

Treatment options for dental abscesses in adulthood include1:

- Root canal cleaning

- Sealing the tooth surface with a dental resin to form a barrier to bacterial penetration

Prevention recommendations include1:

- Rigorous oral hygiene and preventive procedures

- Daily use of fluoride toothpaste adapted to age

- Regular fluoride varnish applications at the dental chair

Quality of life in adults with XLH is affected most negatively by physical function, stiffness, and bodily pain. Impaired quality of life in adult patients may be an indicator of underlying skeletal disease.6

Radiographic imaging

Radiographic imaging can be used to assess the origin of osteoarticular conditions: physical function, pain, and poor quality of life.

Walking ability

6-minute walk test (6MWT): The 6MWT is a practical, simple test that measures how far a patient can walk in 6 minutes on a flat, hard surface.12

Dental

Dental defects have also been shown to impact quality of life.

- See dental assessment

Other quality of life tools

There are several quality-of-life tools that have been used to assess quality of life in adult XLH patients in studies and clinical trials. They include HAQ, SF-36, RAPID 3, and the composite criterion.

Variables associated with worse QOL in adults with XLH using logistic regression13

Biochemical monitoring

Regular monitoring is recommended to avoid hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, nephrocalcinosis, and hyperparathyroidism.1

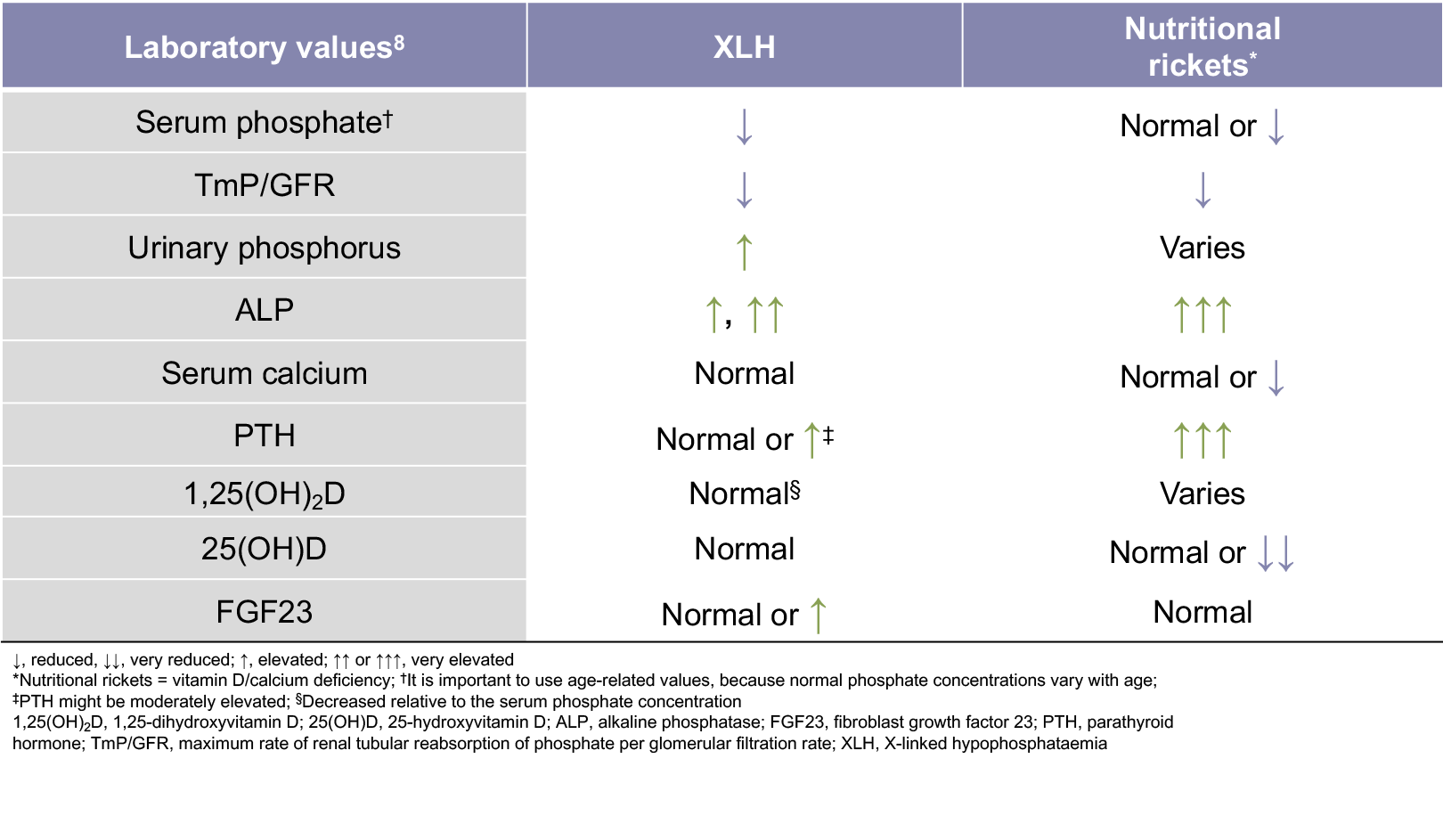

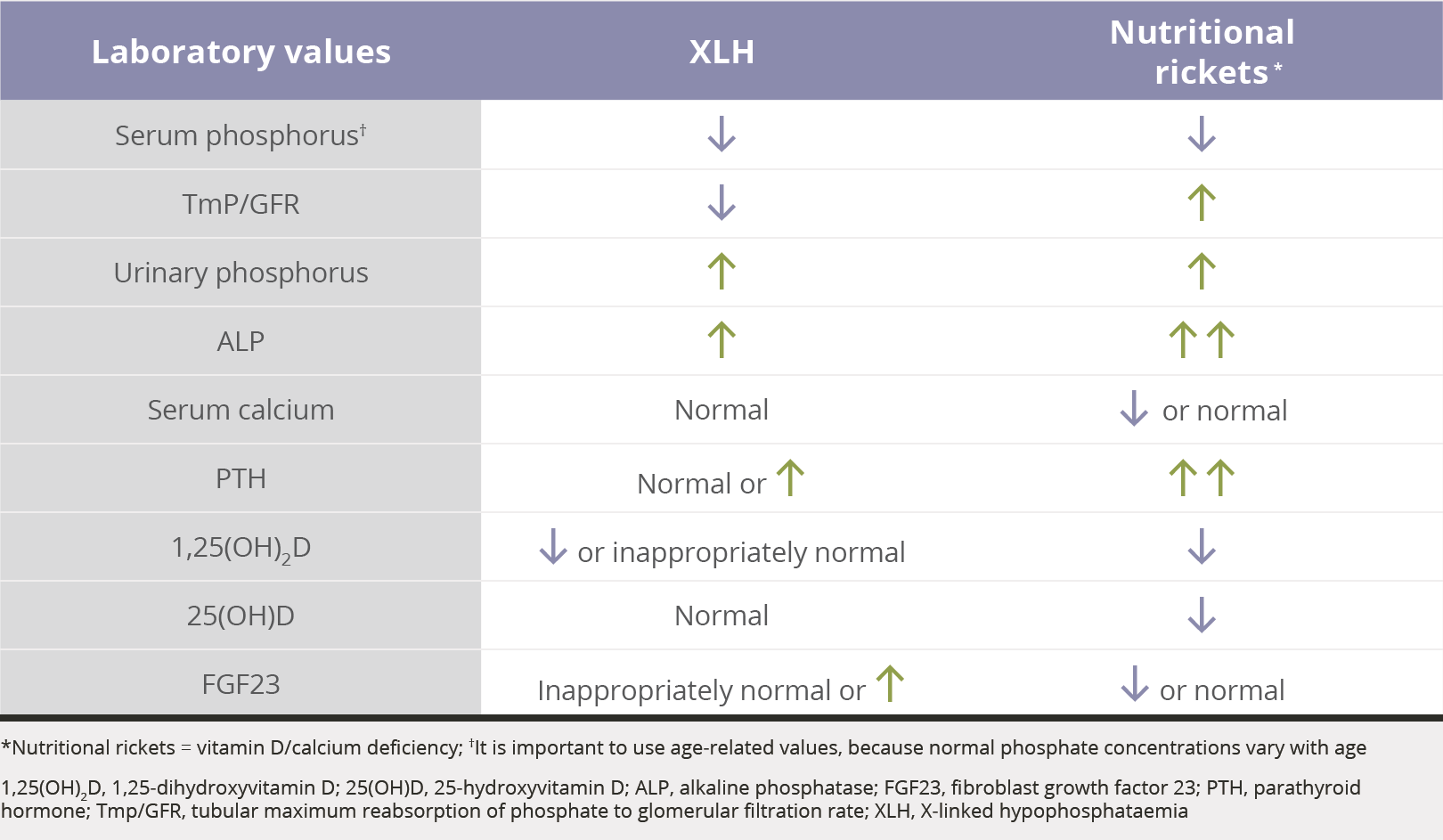

Phosphate reabsorption

The TmP/GFR is the ratio of renal tubular maximum reabsorption of phosphate (TmP) to glomerular filtration rate (TmP/GFR)2,14-22

1. Linglart A, Biosse-Duplan M, Briot K, et al. Therapeutic management of hypophosphatemic rickets from infancy to adulthood. Endocr Connect. 2014;3(1):R13-R30. 2. Ruppe MD. X-linked hypophosphatemia. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al, eds. Gene Reviews. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK83985/. Accessed October 20, 2017. 3. Carpenter TO, Imel EA, Holm IA, Jan de Beur SM, Insogna KL. A clinician's guide to X-linked hypophosphatemia. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(7):1381-1388. 4. Penido MG, Alon US. Phosphate homeostasis and its role in bone health. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27(11):2039-2048. 5. Beck-Nielsen SS, Brusgaard K, Rasmussen LM, et al. Phenotype presentation of hypophosphatemic rickets in adults. Calcif Tissue Int. 2010;87(2):108-119. 6. Skrinar A, Marshall A, San Martin J, Dvorak-Ewell M. X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH) impairs skeletal health outcomes and physical function in affected adults. Poster presented at: Endocrine Society’s 97th Annual Meeting and Expo, March 5-8, 2015. San Diego, CA. 7. Pal R, Bhansali A. X-linked hypophosphatemia with enthesopathy. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;1-2. 8. Karaplis AC, Bai X, Falet J-P, Macica CM. Mineralizing enthesopathy is a common feature of renal phosphate-wasting disorders attributed to FGF23 and is exacerbated by standard therapy in hyp mice. Endocrinology. 2012;153(12):5906-5917. 9. Opsahl Vital S, Gaucher C, Bardet C, et al. Tooth dentin defects reflect genetic disorders affecting bone mineralization. Bone. 2012;50(4):989-997. 10. Carpenter TO. New perspectives on the biology and treatment of X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1997;44(2):443-466. 11. Teeth. Human Anatomy. WebMD Medical Encyclopedia. https://www.webmd.com/oral-health/picture-of-the-teeth#1. WebMD, LLC. 2015. Accesssed December 9, 2017. 12. 6-Minute Walk Test. American Thoracic Society Web site. https://www.thoracic.org/statements/resources/pfet/sixminute.pdf. Accessed November 16, 2017. 13. Che H, Roux C, Etcheto A, et al. Impaired quality of life in adults with X-linked hypophosphatemia and skeletal symptoms. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;174(3):325-333. 14. Payne RB. Renal tubular reabsorption of phosphate (TmP/GFR): indications and interpretation. Ann Clin Biochem. 1998;35(pt. 2):201-206. 15. Santos F, Fuente R, Mejia N, Mantecon L, Gil-Peña H, Ordoñez FA. Hypophosphatemia and growth. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28(4):595-603. 16. Goldsweig BK, Carpenter TO. Hypophosphatemic rickets: lessons from disrupted FGF23 control of phosphorus homeostasis. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2015;13(2):88-97. 17. Imel EA, Zhang X, Ruppe MD, et al. Prolonged correction of serum phosphorus in adults with X-linked hypophosphatemia using monthly doses of KRN23. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(7):2565-2573. 18. Özkan B. Nutritional rickets. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2010;2(4):137-143. 19. Nield LS, Mahajan P, Joshi A, Kamat D. Rickets: not a disease of the past. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(4):619-626. 20. Chong WH, Molinolo AA, Chen CC, Collins MT. Tumor-induced osteomalacia. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2011;18(3):R53-R77. 21. Jan de Beur SM. Tumor-induced osteomalacia. JAMA. 2005;294(10):1260-1267. 22. Halperin F, Anderson RJ, Mulder JE. Tumor-induced osteomalacia: the importance of measuring serum phosphorus levels. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007;3(10):721-725.